Techniques for efficient post-quantum finance (Part 4: reducing storage requirements)

technical research proof-of-stake

23rd June 2022

Table of Contents

This is the fourth article in a multipart series from The QRL Foundation and Geometry Labs exploring various methods for constructing scalable post-quantum technology. In the first article, we describe a lattice-based one-time signature scheme similar to the one published by Lyubashevsky and Micciancio [1], with some optimizations for key and signature sizes. In the second article, we show how to extend this to Boneh and Kim style signature aggregation [2], which has several potential applications such as reducing the on-chain footprint for proof-of-stake consensus with many validators, implementing m-of-n multisignature wallets, and on-chain governance. The third article described our novel one-time adaptor signature scheme, designed to enable payment channels and decentralized trustless cross-chain atomic swaps (inspired by the work of Esgin, Ersoy, and Erkin, [3]).

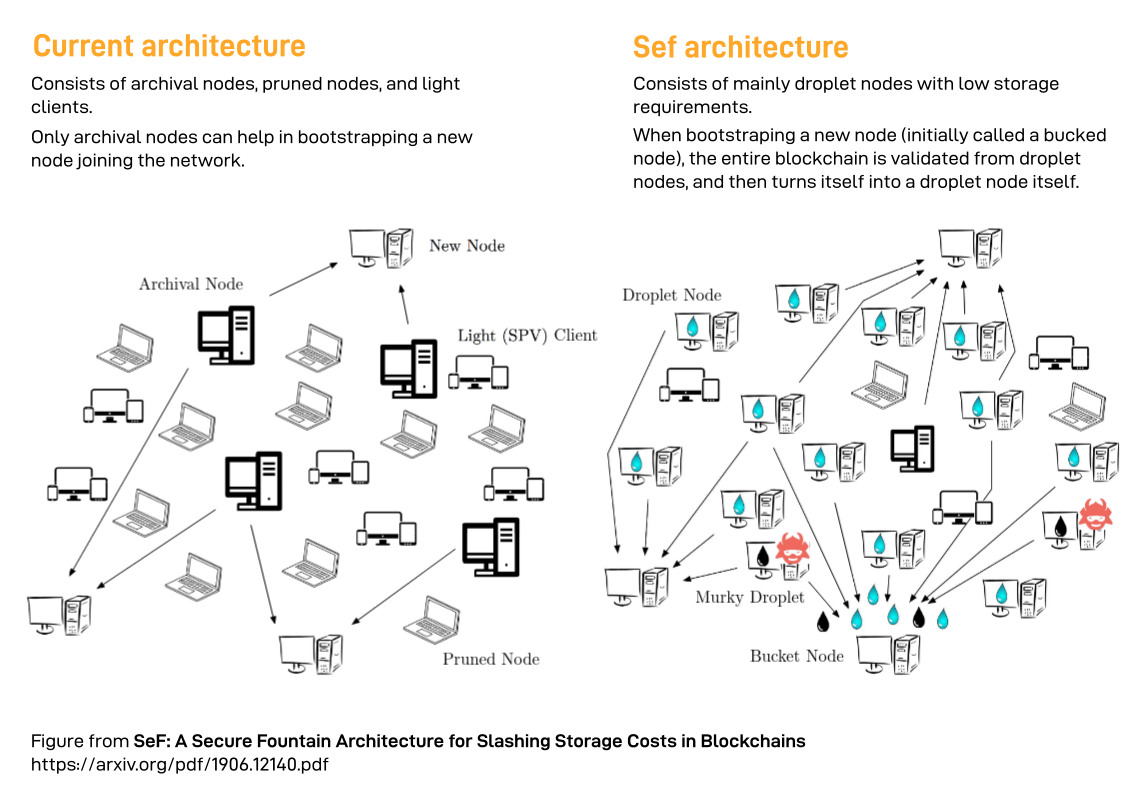

While the previous articles focused on methods for reducing on-chain footprint, we now turn our attention to quantum-resilient off-chain methods for reducing node storage requirements, without compromising blockchain verifiability - even in the presence of malicious actors (see the techniques of [4] and [5]). The approaches discussed here are blockchain-agnostic, and require no changes to the underlying protocol. Since the secure fountain architecture is simply an opt-in decentralized peer-to-peer storage layer, it can be run alongside the existing message distribution and storage system.

The methods described below are constructed with techniques from the mathematical discipline of coding theory; simply by encoding the blockchain locally in a clever way using Luby transform (LT) codes from [5], we can reduce local storage burdens significantly (with error resilience). In particular, we focus on the secure fountain architecture of [4] and compare it to the popular non-coding-theory-based approaches. Making near-optimal space/bandwidth tradeoffs enables a dramatic (orders of magnitude) reduction in storage requirements. This system is secure in the presence of quantum adversaries as long as a quantum-resilient hash function is used.

Note: While some effort has gone into making everything understandable, the intended audience for this article series is systems integrators and students in cryptography. In order to help aid in understanding, we have an open AMA form for the duration of this “Techniques for post-quantum finance” series to ask any questions that may arise, both technical and non-technical. These writeups are intended to be informational, and the schemes described for illustration are not formal secure specifications.

Fundamental Tradeoff

The secure fountain architecture decreases storage requirements at the expense of increasing the “bootstrap cost”, which measures the cost of bringing a new full node from the genesis block all the way up to the tip of the main chain. One way to measure bootstrap cost is the total number of peers that a new full node must communicate with before being brought up to date.

If each node stores a fraction $1/\gamma$ of the total blockchain, then each new full node will have to talk to at least $\gamma$ new nodes before they can be brought up to date. That would be the best case scenario in an information-theoretic sense, meaning that this is the optimal tradeoff between bootstrap cost (measured by total number of nodes to talk to) and proportional space savings. The Secure Fountain Architecture described in [4] and below is a practical implementation that is extremely close to this theoretical optimal boundary.

Comparison to Other Methods: SPV and Pruning

Two approaches for reducing storage burdens in decentralized finance are currently popular: simplified payment verification (SPV) and block pruning. In SPV systems, light clients store only block headers, erasing block data locally. In block pruning systems, light clients store full block data for only a subset of the blockchain, verifying transactions for only the part of the blockchain they have stored (or downloading other parts of the blockchain from peers on an as-needed basis).

Unfortunately, SPV does not help full nodes or impact the bootstrap cost at all. Moreover, SPV has some associated security risks that reduce its suitability for use cases related to scaling decentralized finance protocols (see [4]). Block pruning has improved security guarantees compared to SPV and can improve bootstrap costs. However, suboptimal implementations can have an enormous bootstrap cost compared to the information-theoretic minimum $\gamma$. For example, consider a naive case where block pruning is carried out every $k = 10,000$ blocks by independently sampling $s = 1$ block uniformly at random to retain (and deleting the other $9,999$ blocks). The storage savings are $\gamma = k/s = 10000$-fold, and in an optimal world, we only need to contact $10,000$ different nodes to complete our collection. Unfortunately, in practice we would need to contact (in expectation) many many more than $k=10,000$ new nodes in order to bootstrap, a result from the so-called “coupon collector’s” problem [6]: if each box of a brand of cereal has a toy in it, and there are $n$ different types of toys, how many boxes will we likely need to buy to obtain the whole collection?

Fountains and Droplets

The idea behind the secure fountain architecture can be visualized nicely: nodes encode an epoch of blocks (say $10,000$) into a droplet, or a coded block, which we will describe in a moment, and new nodes hold out a bucket (downloading droplets) until more drops have been collected than the size of the bucket. From the downloaded droplets, the new full node can decode the droplets using a peeling decoder into the missing epoch. The droplets are decoded into the epoch of blocks, one block at a time, resistant to errors. Using a chain of block header hashes, new full nodes can even identify maliciously formed droplets and ignore their data! Everything from the epoch can be erased, except the block headers and one coded block (droplet).

With this system, portions of the blockchain can be bootstrapped from “droplet” nodes for new “bucket” nodes at the cost of bandwidth overhead and communication costs with droplet nodes, and bucket nodes can turn themselves into droplet nodes after bootstrapping, reducing their local storage costs. The notion is that if the $k$ blocks in a certain epoch have not been referenced for a certain period of time, then that epoch can be stored as $s$ droplets and deleted. If a new transaction is observed that references a deleted epoch, the node can merely re-bootstrap. This way, frequently-used epochs are never deleted, infrequently-used epochs find themselves deleted occasionally only to be re-bootstrapped later, and dormant epochs tend to stay deleted.

One characteristic that the secure fountain architecture has in common with both SPV and pruning is that the block header hash chain is preserved in all three approaches. However, the secure fountain architecture is different from SPV because SPV nodes do not store block data, and it is also different from pruning, which entirely “forgets” parts of the blockchain. This contrasts with the secure fountain architecture, where full nodes encode a subset of an epoch into droplets and erase everything except their droplets (and the chain of block headers). Due to this, we can attain near-optimal bootstrap costs.

How does the Secure Fountain Architecture Work?

There are two steps to the secure fountain architecture: encoding and decoding. Encoding is based on the Luby Transform (LT) code from [5]. We save the header chain and replace a chain of blocks with (i) a set of bitwise XORs of the input blocks and (ii) enough data to determine which blocks are included in which XORs.

- System parameters $k = 1, 2, 3, …$ and $s = 1, 2, …, k$ are set.

- The $\ell^{th}$ epoch, which consists of $k$ blocks $B_{\ell k}, B_{\ell k + 1}, \ldots, B_{(\ell+1) k - 1}$, is encoded into $s$ new droplets, $C_{\ell s}, C_{\ell s + 1}, \ldots, C_{(\ell + 1)s - 1}$. To compute each $C_j$, the encoder works as follows.

- Sample a degree $d = 1, 2, …, k$ from the Robust Soliton Distribution, independently from all other randomness; see [4] and [5].

- Sample $d$ indices uniformly without replacement from $\left\{\ell k, \ell k + 1, \ldots, (\ell + 1)k - 1\right\}$, call them $i_0, i_1, \ldots, i_{d-1}$.

- Set $\nu_j$ to be the length-$k$ characteristic bitstring describing these indices.

- Set $C_j = (\nu_j, \otimes_{i=i_0, i_1, \ldots, i_{d-1}} B_i)$ where $\otimes$ denotes the bitwise XOR of the block data.

- Save the block header chain from $B_{\ell k}, B_{\ell k + 1}, \ldots, B_{(\ell+1) k - 1}$, written as $h_{\ell k}, h_{\ell k + 1}, \ldots, h_{(\ell + 1)k - 1}$.

- Store $((h_{\ell k}, h_{\ell k + 1}, \ldots, h_{(\ell + 1)k - 1}), C_{\ell s}, C_{\ell s + 1}, l\ldots, C_{(\ell + s)s - 1})$.

- Erase $B_{\ell k}, B_{\ell k + 1}, \ldots, B_{(\ell+1) k - 1}$.

Decoding requires knowing the header chain $h_{\ell k}, h_{\ell k + 1}, \ldots, h_{(\ell + 1)k - 1}$, which can be obtained in the usual way. Decoding their contents is a matter of playing a matching game [7] and checking the chain of block headers and Merkle roots. To carry this out,

- Contact an arbitrary subset of at least $k$ nodes and download their droplets, say $n$ nodes and $ns$ droplets.

- Make a bipartite graph with block indices in one part and droplets in the other part, drawing an edge between a block index and a droplet if the characteristic vector of the droplet indicates the block is included in that droplet.

- Find a droplet, say $C_\ell$, connected to exactly one block, say $B_m$. Call such droplets singletons. If no such droplet can be found, terminate. Note that if a droplet is connected to only one block, then the droplet is the bitwise XOR of only one block, so singleton droplets are just plain blocks.

- For this droplet, treat it like a block and compute the Merkle root of the transactions. If the header of this droplet does not match the corresponding header $h_j$ in the chain, or the Merkle root of this block does not match the Merkle root inside this header, the droplet is rejected and deleted from the graph together with its adjacent edges.

- Otherwise, the droplet is accepted. In this case, set $\widehat{B}_m := C_\ell$. Then, for each other droplet connected to $B_m$, say $C_\ell^\prime$, we reset $C_\ell^\prime \leftarrow C_\ell^\prime \widehat{B}_m$. Then we delete $B_m$ from the graph together with its adjacent edges, and go back to step (2).

For a simple toy example with nice diagrams explaining the process, see [4].

If decoding terminates without all the blocks in the epoch decoded, a procedure described in [4] can be employed to continue downloading new droplets until the blockchain is successfully decoded.

The heavy lifting in [4] and [5] lies in deciding on the degree distribution for $d$, performance analysis, and proving the algorithm is resistant to malicious actors, up to the security notions described below.

An Aside: “big O” Notation and its Caveats

The theorems we use to establish parameters and measure performance are “big O” statements, to give an intuition for complexity. These aren’t very strong statements, in general, and the specific examples presented here are toy examples only because of this. Here we try to provide the reader some intuition for why big O notation is tricky, since it is used in describing the security.

A function $f(x)$ is $O(g(x))$ if and only if there exists constants $M > 0$ and $z \in \mathbb{R}$ such that $M > 0$ and $\left|f(x)\right| \leq M\left|g(x)\right|$ for every $x \geq z$. For example, consider the statement: “$f(x) = 2^{128} \log_2(x)$ is $O(x)$.” For this $f(x)$, we can use $M=1$ and observe that $0 < f(x) \leq x$ for any $x \geq 45964540800636209072203161956181667065928$, a somewhat absurd number. Or, we can observe that $0 < f(x) \leq 2^{128}x$ for all $x > 0$ and use $M = 2^{128}$, a similarly absurd number.

We can informally think of the “strength” of a big O statement as related to the size of the constants $M$ and $z$. The closer we can make $M$ to zero and $z$ to $-\infty$, the stronger the statement. Thus, the statement “$f(x)$ is $O(x)$” is subjectively “weak,” because both $2^{128}$ and $10^{40}$ are large numbers.

A keen-eyed reader will notice that “$f(x) = \log_2(x)$ is $O(x)$” is also true, and seems to be a stronger statement than “$f(x) = 2^{128} \log_2(x)$ is $O(x)$.” Indeed, for the former to be true, we just need $M \geq 1$ and $z > 0$.

The main takeaway is this: without specifying the constants $M$ and $z$, it is not safe to merely replace $O(g(x))$ in a theorem statement with $g(x)$, in general.

Security

The adversary in the Secure Fountain Architecture paper [4] has the goal of convincing a new honest node to decode an incorrect blockchain. The adversary’s capabilities are modeled as follows.

- Honest nodes will always respond with their droplets when contacted by a new bucket node; malicious nodes may stay silent.

- The adversary can respond with arbitrary values for their droplets $C_\ell$, which may or may not be the bitwise XOR of blocks, whether honest or not. These droplets are called murky.

- The adversary may select arbitrary degrees $d$ or arbitrarily select the contributing $d$ blocks to a droplet. These droplets are called opaque.

We assume the network has a random topology, in the sense that if the proportion of honest nodes is $\sigma$ and a node contacts $N$ droplet nodes, then at least $N(1-\sigma)$ of these nodes are honest, in expectation. That is to say, the adversary cannot simply “surround” a node. We note that even in the standard Bitcoin model, an adversary capable of surrounding a node is capable of convincing that node to use an incorrect blockchain, so these assumptions are not unreasonable.

Against an adversary with these capabilities, the authors of [4] prove the following.

Theorem: Let $0 < \delta < 1$. If a bucket node contacts an arbitrary set of droplet nodes and at least $\frac{1}{s}\left(k + O(\sqrt{k}\ln(k/\delta)^2)\right)$ of those nodes are honest, then the probability that the error-resilient peeling decoder fails to recover the entire blockchain is at most $\delta$.

In short, this theorem tells us how many honest droplet nodes we need to contact before a malicious node can no longer prevent us from decoding the entire blockchain. However, notice the big O term $O(\sqrt{k}\ln^2(k/\delta))$ and recall from the above caveat it is not necessarily safe to replace $O(\sqrt{k}\ln^2(k/\delta))$ with $\sqrt{k}\ln^2(k/\delta)$ without a further analysis of [4] and [5].

We can, however, say that if $B_\delta$ is the bootstrap cost (the number of honest droplet nodes we must contact to bootstrap with failure probability $\delta$), then there is a suitably large $M$ such that $\left|B_\delta - \frac{k}{s}\right| \leq M\left|\sqrt{k}\ln(k/\delta)^2\right|$ for all suitably large $k$. Moreover, $k/s$ is the optimal value from the tradeoff in the introduction. So, in practice, $B_\delta > k/s$ and we can ditch the absolute values on the left-hand side. And, of course, $\sqrt{k} > 0$ whenever $k > 0$, and the same can be said of $\ln(k/\delta)^2$. Thus, we have a constant $M > 0$ such that $k/s \leq B_\delta \leq k/s + \frac{M}{s}\sqrt{k}\ln(k/\delta)^2$ for all suitably large $k$.

Examples

For illustration, we consider two toy examples:

Example 1: Let $s = 2^7$ and $\delta = 1/2$. For whichever $M$ we have, if it turns out that $k = 2^{10}$ is sufficiently large (and this could be a big if!), then the chain of inequalities $k/s \leq B_\delta \leq k/s + \frac{M}{s}\sqrt{k}\ln(k/\delta)^2$ becomes $8 \leq B_\delta \leq 8 + \frac{3872M}{128}\ln(2)^2 \approx 8 + 14.5337 M$. If $M = 1$ works, this implies that the bootstrap cost is no more than $23$, indicating that contacting as few as $23$ honest droplet nodes is sufficient to decode the blockchain with probability $1/2$. In this case, we would have $\gamma = k/s = 1024/128 = 8$-fold space savings over a naive storage scheme.

Example 2: Let $s = 2^{12}$ and $\delta = 2^{-10}$. For whichever $M$ we have, if $k = 2^{16}$ is sufficiently large (and, again, this could be a big if!), then the chain of inequalities becomes $64 \leq B_\delta \leq 64 + \frac{323M}{2}\ln(2)^2 \approx 64 + 77.59M$. If $M = 1$ works, then the bootstrap cost is no more than $142$, indicating that contacting $142$ honest droplet nodes is sufficient to decode the blockchain with probability at least $1023/1024 \approx 0.999$. In this case, we would have $\gamma = k/s = 2^{16}/2^{12} = 16$-fold space savings over a naive storage scheme.

Note that these are toy examples that use $M=1$, which may not be the case. Furthermore, it is not guaranteed that for whichever $M$ does work, that $k = 2^{16}$ is sufficiently large.

Performance

We make the following assumptions.

- The characteristic vectors are small compared to block sizes (this is a safe assumption).

- The adversary does not have control over the topology of the network.

- A proportion $0 < \sigma < 1$ of nodes are malicious.

Now, under these assumptions, and forgetting the computations necessary for computing Merkle roots (since these must be computed for verifying transactions anyway), the authors of [4] prove the following theorem.

Theorem: Given $k, s, \delta, \sigma$, secure fountain architectures have $\gamma = k/s$ storage savings, $\frac{1}{s}\left(k + O(\sqrt{k}\ln^2(k/\delta))\right)$ bootstrap cost, $O(\frac{\ln^2(k/\delta)}{(1-\sigma)\sqrt{k}})$ bandwidth overhead, an encoding cost that is $O\left(\frac{s\ln(k/\delta)}{k}\right)$, and a decoding cost that is $O\left(\frac{\ln(k/\delta)}{1-\sigma}\right)$.

To understand the ramifications of this theorem, consider our earlier examples.

Example 1:

For $k = 2^{10}$, $s = 2^7$, $\delta = 1/2$, $M=1$, we saw we had the bootstrap cost $23$. For this example, we have the bandwidth overhead: $O\left(\frac{\ln^2(k/\delta)}{(1-\sigma)\sqrt{k}}\right)$. This is another big O notation, introducing a second pair of constants $M^\prime$ and $z^\prime$, such that $\texttt{bandwidth_overhead} \leq M^\prime\left|\frac{\ln^2(k/\delta)}{(1-\sigma)\sqrt{k}}\right|$ for all $k > z^\prime$. However, even if $M = 1$ worked before, and even if $k = 2^{10}$ was sufficiently large before, there is no guarantee here that $k > z^\prime$ for whichever $M^\prime$ we have, or even that $M^\prime = 1$ can work.

Assuming $M^\prime = 1$ works, and assuming that $k = 2^{10}$ is sufficiently large for this $M^\prime$ (these are possibly very strong assumptions), we have $\texttt{bandwidth_overhead} \leq 1.817/(1-\sigma).$ Assuming $\sigma \leq 1/3$, $(1-\sigma)^{-1} \geq 2/3$, the upper bound on bandwidth overhead is at least $2.7255$. Assuming this upper bound is tight enough to be attained, this means that a bootstrapping node, in expectation, needs to download at least $273%$ more data than in the full-node model (where all nodes store all data), and contact at least $23$ honest droplet nodes while doing so, in order to have a $1/2$ probability of successfully decoding the blockchain.

In summary, nodes in the above example would have to download $2.73$ times more data than in the full-node approach in order to bootstrap, and need to contact $23$ honest droplet nodes, but would enjoy $8$-fold space savings over the full-node approach once they are caught up.

In the next example, nodes have to download $1.9$ times more data than in the full-node model in order to bootstrap, and need to contact $142$ honest droplet nodes, but would enjoy $16$-fold space savings over the full-node approach.

Example 2:

For $k = 2^{16}$, $s = 2^{12}$, $\delta = 2^{-10}$, $M = 1$, we saw we had a bootstrap cost $142$. For this example, we have the bandwidth overhead $O\left(\frac{\ln^2(k/\delta)}{(1-\sigma)\sqrt{k}}\right)$. As before, this is another big O notation, so we have that $\texttt{bandwidth_overhead} \leq M^\prime\left|\frac{\ln^2(k/\delta)}{(1-\sigma)\sqrt{k}}\right|$ for all $k > z^\prime$.

Assuming $M^\prime = 1$ works and that $k = 2^{16}$ is sufficiently large for this $M^\prime$ (again, these are possibly very strong assumptions), we have $\texttt{bandwidth_overhead} \leq 1.269/(1-\sigma)$. Again assuming $\sigma \leq 1/3$, the upper bound on our bandwidth overhead is at least $1.902$. Assuming this upper bound can be attained, this means a bootstrapping node, in expectation, needs to download $190%$ more data than in the full-node model, and needs to contact $142$ honest droplet nodes while doing so, in order to have a $1/1024$ probability of failing to decode the blockchain.

The authors of [4] targeted even more dramatic tradeoffs, stating that their secure fountain “codes tuned to achieve 1000x storage savings enable full nodes to encode the 191GB Bitcoin blockchain into 195MB on average” while enabling a new node to sync up by connecting to approximately 1,100 honest nodes (at the time of writing there are approximately 16,000 reachable Bitcoin nodes per bitnodes.io).

Conclusion

The approaches discussed here are blockchain agnostic techniques to offload the storage burden on nodes to bandwidth overhead. The approach can work with almost every major cryptocurrency today, as an optional protocol that can be run on top of the consensus layer, including QRL, Ethereum, Zcash, Monero, and Bitcoin. Given a quantum-secure hash function (such as the ones used in the QRL protocol) the system is robust in the presence of practical quantum adversaries.

Writeup Contributors

Brandon Goodell, Mitchell “Isthmus” Krawiec-Thayer

Correspondence: info@geometrylabs.io

Works Cited

[1] Lyubashevsky, Vadim, and Daniele Micciancio. “Asymptotically efficient lattice-based digital signatures.” Theory of Cryptography Conference. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2008.

[2] Boneh, Dan, and Sam Kim. “One-Time and Interactive Aggregate Signatures from Lattices.” (2020). https://crypto.stanford.edu/~skim13/agg_ots.pdf

[3] Esgin, Muhammed F., Oğuzhan Ersoy, and Zekeriya Erkin. “Post-quantum adaptor signatures and payment channel networks.” European Symposium on Research in Computer Security. Springer, Cham, 2020.

[4] Kadhe, Swanand, Jichan Chung, and Kannan Ramchandran. “SeF: A secure fountain architecture for slashing storage costs in blockchains.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1906.12140 (2019).

[5] Luby, Michael. “LT codes.” The 43rd Annual IEEE Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, 2002. Proceedings. IEEE Computer Society, 2002.

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coupon_collector%27s_problem

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Graph_matching

This article is part of the Techniques for efficient post quantum finance series.

- Introducing lattice-algebra: An elegant, high-performance post-quantum cryptography library

- Techniques for efficient post-quantum finance (Part 1: digital signatures)

- Techniques for efficient post-quantum finance (Part 2: signature aggregation)

- Techniques for efficient post-quantum finance (Part 3: adaptor signatures)

- Selected: Techniques for efficient post-quantum finance (Part 4: reducing storage requirements)

Proof of Stake technical research

23rd June 2022