Techniques for efficient post-quantum finance (Part 2: signature aggregation)

technical research proof-of-stake

28th April 2022

Table of Contents

This is the second article in a multipart series from The QRL Foundation and Geometry Labs exploring various methods for constructing scalable post-quantum cryptographic primitives and protocols. In the last article, we describe a lattice-based one-time signature scheme similar to the one published by Lyubashevsky and Micciancio, with some optimizations for key and signature sizes. In this article, we show how to extend this to Boneh and Kim style signature aggregation, which has several potential applications such as reducing the on-chain footprint for proof-of-stake consensus with many validators, implementing m-of-n multisignature wallets, and on-chain governance. The next article describes our novel one-time adaptor signature scheme, designed to enable payment channels and decentralized trustless cross-chain atomic swaps (inspired by the work of Esgin, Ersoy, and Erkin).

The articles in this series describe the applications and security models; additionally, open-source python implementations of the cryptography are freely available via GitHub and PyPI (pip install lattice-cryptography), built with the lattice-algebra library described in a previous QRL blog post.

Note: While some effort has gone into making everything understandable, the intended audience for this article series are systems integrators and students in cryptography. In order to help aid in understanding, we’ve added a further reading and materials section and will have an open AMA form for the duration of this “Techniques for post-quantum finance” series to ask any questions that may arise, both technical and non-technical. These writeups are intended to be informational, and the schemes described for illustration are not formal secure specifications.

Extending Digital Signatures to Aggregatable Signatures

Aggregatable signatures have a simple goal: minimize storage requirements for authentication processes by compactly describing several signatures in one verifiable aggregated signature. Before describing aggregation, we recap the general notion of a cryptgraphic signature (as described in the last article).

A digital signature scheme refers to a tuple of algorithms (Setup, Keygen, Sign, Verify) which informally work as follows.

- $\texttt{Setup}(\lambda) \to \rho$. Input a security parameter $\lambda$, typically indicating the number of bits of security, and outputs some public parameters, $\rho$. Typically, $\rho$ contains a description of a secret signing key set, $K_S$, a public verification key set, $K_V$, a message set $M$, and a signature set $S$. $\texttt{Setup}$ is usually run by all parties before participating. The input and output of $\texttt{Setup}$ are both public.

- $\texttt{Keygen}(\lambda, \rho) \to (sk, vk)$. Input $(\lambda, \rho)$ and output a new random keypair $(sk, vk) \in K_S \times K_V$, where $sk$ is a secret signing key and $vk$ is the corresponding public verification key.

- $\texttt{Sign}(\lambda, \rho, (sk, vk), \mu) \to \xi$. Input $(\lambda, \rho, (sk, vk), \mu)$ where $\mu \in M$ is a message, and outputs a signature, $\xi \in S$.

- $\texttt{Verify}(\lambda, \rho, vk, \mu, \xi) \to b \in \{0, 1\}$. Output a bit $b$ indicating whether the signature is a valid signature on the message $\mu$ with the public verification key $vk$.

As in the last article, we assume that the message set $M$ is the set of all $k$-length bit strings, $M = \{0,1\}^k$ where $k$ is an (integral valued) function of $\lambda$. Since $\lambda$ and $\rho$ (the input and output of $\texttt{Setup}$, respectively) are shared parameters known by all participants, we will omit them as inputs below for readibility. Moving onto aggregation, our goal is to take a typical signature scheme as a sub-scheme and add support for an $\texttt{Aggregate}$ function and an $\texttt{AggregateVerify}$ function that work roughly as follows.

- $\texttt{Setup}^\prime$ augments the output of $\texttt{Setup}$ with an aggregation capacity $C$ and an aggregate signature set $\Xi_{ag}$.

- $\texttt{Aggregate}((\mu_i, vk_i, \xi_i)_{i=0}^{N-1}) \to \texttt{out} \in \Xi_{ag} \cup \{\bot\}$. Input a list of message-key-signature triples $(\mu_0, vk_0, \xi_0), …, (\mu_{N-1}, vk_{N-1}, \xi_{N-1}) \in M \times K_V \times \Xi$ and output an aggregate signature $\texttt{out} = \xi_{ag} \in \Xi_{ag}$ or a distinguished failure symbol, $\texttt{out} = \bot$.

- $\texttt{AggregateVerify}((\mu_i, vk_i)_i, \xi_{ag}) \to b \in \{0,1\}$. Input a list of messages-key pairs $(\mu_0, vk_0) , …, (\mu_{N-1}, vk_{N-1}) \in M \times K_V$ and an aggregate signature $\xi_{ag} \in \Xi_{ag}$ and output a bit $b$ indicating whether $\xi_{ag}$ is a valid aggregate signature on these message-key pairs.

If aggregation of signatures requires the participation (and secret signing keys) of all the signers in one or more round of interaction, the scheme is called interactive, otherwise it is called non-interactive.

There is some redundancy built into this definition. We denote an aggregate signature scheme with the tuple of algorithms $(\texttt{Setup}^\prime, \texttt{Keygen}, \texttt{Sign}, \texttt{Verify}, \texttt{Aggregate}, \texttt{AggregateVerify})$, but often $\texttt{Verify}$ is disregarded. After all, a signature $\xi \in \Xi$ on some $\mu \in M$ under $vk \in K_V$ can be ‘aggregated’ alone by computing $\xi_{ag} = \texttt{Aggregate}(\mu, vk, \xi)$, so that $\texttt{Verify}$ is subsumed by $\texttt{AggregateVerify}$. However, in practice, there may be situations where aggregating a signature alone is wasteful of computational time or space, and thus verification of individual signatures may have use cases, which is why we include it in our definition. However, we avoid basing our security properties below on the $\texttt{Verify}$ algorithm, to avoid redundancy and unnecessary security proofs.

Just like in the previous article, this framework is only secure if both the functions and their parameters are carefully selected. For illustration, suppose $\Xi_{ag} = \{0, 1\}$; with single bit signatures, it would take at most two tries to produce a forgery! Or consider the situation if $\texttt{AggregateVerify}$ was a function that returns $1$ for most combinations of inputs; in this case a signature being ‘valid’ would provide little assurance of security. This leads us extend the discussion to the security properties of aggregate signature schemes.

Correctness

Correctness means that honestly computed signatures have to pass aggregate verification. In other words, if $1 \leq N \leq C$ and, for each $i = 0, 1, \ldots, N-1$, each $(sk_i, vk_i) \leftarrow \texttt{Keygen}$, each $\mu_i \in M$, and each $\xi_i \leftarrow \texttt{Sign}((sk_i, vk_i), \mu_i)$, and $\xi_{ag} \leftarrow \texttt{Aggregate}((\mu_i, vk_i, \xi_i)_{i=0}^{N-1})$, then $\texttt{AggregateVerify}((\mu_i, vk_i)_{i=0}^{N-1}, \xi_{ag}) = 1$.

Aggregate Existential Unforgeability

The definition of existential unforgeability introduced in the previous article does not carry over to aggregate signatures exactly, although with a few modifications, we obtain the following unforgeability game.

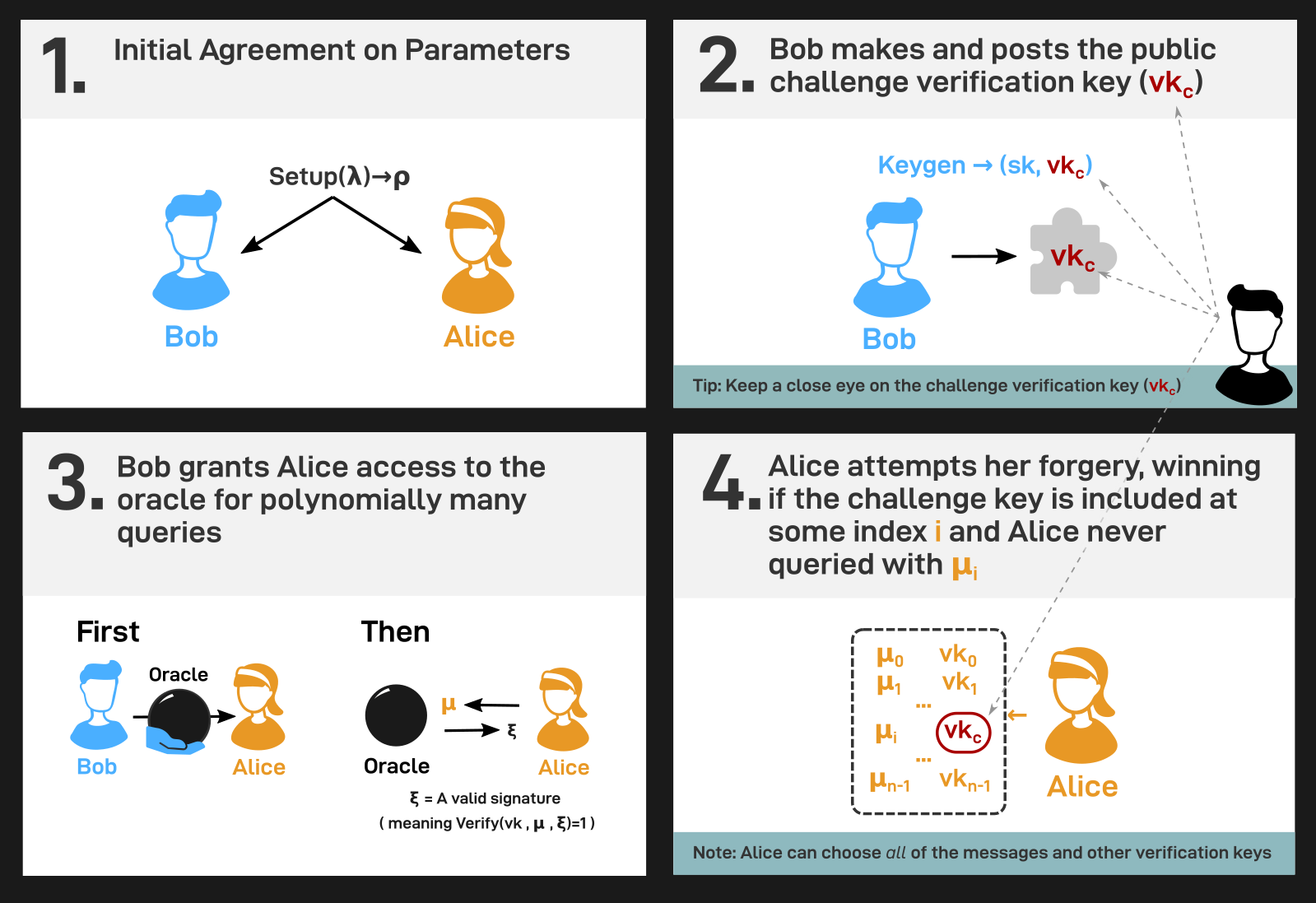

- First, Alice and Bob agree upon input and output of $\texttt{Setup}^\prime$, to recreate the common situation that Alice and Bob have agreed upon some publicly audited and cryptanalyzed signature scheme (e.g. by the NIST standardization process).

- Next, Bob runs $\texttt{Keygen}$ to get some challenge keys $(sk, vk)$. Bob sends $vk$ to Alice.

- Bob grants Alice access to a signature oracle; upon querying this oracle with any $\mu \in M$, Alice receives in return an (unaggregated) $\xi \in \Xi$ such that $\texttt{Verify}(vk, \mu, \xi) = 1$. Alice can make queries adaptively in any order she likes, and decide on these queries after seeing other oracle query responses.

- Lastly, Alice outputs either a distinguished failure symbol $\bot$ or a purported forgery $\texttt{forgery} = ((\mu_i, vk_i)_{i=0}^{N-1}, \xi_{ag}) \in (M \times K_V)^N \times \Xi_{ag}$ for some $1 \leq N \leq C$. Alice’s forgery is successful if $\texttt{AggregateVerify}(\texttt{forgery}) = 1$ and there exists an index $i \in \{0, 1, \ldots, N-1\}$ such that

- $vk_i = vk$, the challenge key, and

- the signing oracle was not queried with $\mu_i$.

This game is summarized in the following diagram.

When is Aggregation Advantageous?

Compact Aggregation: To glue or not to glue?

You may have noticed that we can non-interactively aggregate signatuers by merely concatenating (i.e. glueing) them together. In other words, if $\xi_i$ is a purported signature on some message $\mu_i$ under a verification key $vk_i$ for each $i = 0, 1, \ldots, N-1$, then we could define the following.

- $\texttt{Aggregate}$ inputs $(\mu_0, vk_0, \xi_0), …, (\mu_{N-1}, vk_{N-1}, \xi_{N-1})$ and outputs the $N$-tuple $\xi_{ag} = (\xi_0, …, \xi_{N-1})$.

- $\texttt{AggregateVerify}$ inputs a list of messages-key pairs $(\mu_0, vk_0), …, (\mu_{N-1}, vk_{N-1})$ and an aggregate signature $\xi_{ag}$. Parse $\xi_{ag} = (\xi_0, …, \xi_{N-1})$, compute each $b_i = \texttt{Verify}( \mu_i, vk_i, \xi_i)$, and return $b_{0} \cdot b_{1} \cdot \ldots \cdot b_{N-1}$.

We note that the size of the aggregate signature is exactly $N$ times the size of an individual signature $\xi_i$. That is to say: $|\xi_{ag}| = O(N)$. This mode of aggregation linear or trivial aggregation, because we can always perform it with any signature scheme.

This leads us to the notion of compact aggregatable signatures. These are exactly the aggregate signature schemes such that the size of an aggregate signature is sublinear in $N$. In other words, these are the aggregatable signature schemes for which it is (asymptotically) more efficient to publish aggregated signatures than to publish individual signatures.

Assessing the Benefits and Drawbacks

Even if a scheme is a compact aggregatable signature scheme (say with $|\xi_{ag}| = O(lg(N))$), then the actual constants wrapped up in the big O notation here critically determine whether the scheme is actually practical.

For example, in the CRYSTALS-Dilithium signature scheme, which is one of the leading NIST post-quantum standard signature candidates, we see keys at the highest security level that are $2592$ bytes, and signatures that are $4595$ bytes. As a reality check, it is clear that if we have equally sized keys, then just so long as an aggregate of two signatures is smaller than $9190$ bytes, then it is more space efficient to aggregate signatures.

Using the same reasoning, publishing $N$ CRYSTALS signatures and keys takes up $7551 N$ bytes. We can compare naively stacking CRYSTALS-Dilithium signatures against a logarithmically-sized aggregate signature scheme. In fact, we always need to store keys, and we have $N$ of these, perhaps of size $a$ bytes. And we know that the aggregate signature is $O( lg(N))$ bytes, so the cost of $N$ keys and one aggregate signature asymptotically approaches $aN + b \cdot lg(N)$ for a constant $b$. Moreover, it is only worth using this logarithmically sized aggregate signature scheme if $aN + b \cdot lg(N) < 7551 N$, and even then only if we can make $N$ sufficiently large. Taking these factors into consideration, there are four possible scenarios:

- if $a >= 7551$ aggregation is not an improvement over trivial stacking.

- if $a < 7551$ but $b > (7551-a)N/log(N)$ aggregation is not an improvement over trivial stacking.

- if $a < 7551$ and $b < (7551-a)N/log(N)$ aggregation is more space-efficient than trivial stacking. However when $aN + b \cdot lg(N) < 7551 N$ by a small margin the space savings may not be significant.

- if $a < 7551$ and $b < (7551-a)N/log(N)$ and $aN + b \cdot lg(N) < 7551 N$ by a large margin, aggregation may offer significant space savings.

Note that overall evaluation should also take into account time complexity, which is discussed below in the “Verification Overhead” section.

Case Study: Boneh-Kim-Lyubashevsky-Micciancio Signatures

In [1], Lyubashevsky and Micciancio introduced asymptotically efficient lattice-based digital signatures. In [4], Boneh and Kim formalized a one-time, non-interactive aggregatable signature scheme based on these signatures. While comparing one-time signatures to many-time signature schemes is a bit of an apples-to-oranges comparison, we hope the reader is patient with us while we compare fruit.

Setting some details aside, we can loosely think of the Lyubashevesky-Micciancio signatures roughly as follows: a signing key is a pair of small-norm vectors $sk = (\underline{x}, \underline{y})$ in a public lattice which has a challenge vector $a$ part of its public parameters. The verification key is $vk = (X, Y) = (\langle \underline{a}, \underline{x} \rangle, \langle \underline{a}, \underline{y} \rangle)$. To sign a message $\mu$, a user hashes it to get a small-norm challenge $c$ and computes $\xi = \underline{x}\cdot c +\underline{y}$. Since dot products are linear, anyone can check that $\langle \underline{a}, \xi \rangle = v \cdot c + u$, and since $\underline{x}$, $\underline{y}$, and $c$ all have small norms, anyone can check that the signature also has a small norm. On the other hand, if an algorithm that has no information about $sk$ can output any vector $z$ such that $\langle \underline{a}, \underline{z} \rangle = X \cdot c + Y$, then we can use that algorithm to construct a solution to a cryptographically hard problem.

Again setting some details aside, we can loosely think of the Boneh-Kim aggregatable extension of these signatures as follows. To aggregate signatures, some small-norm aggregation coefficients are computed, $\underline{t} = (t_{0}, …, t_{N-1}) = hash(salt, (\mu_0, vk_0), …, (\mu_{N-1}, vk_{N-1}))$. From these, $\texttt{Aggregate}$ merely outputs the linear combination of signatures, $\xi_{ag} = t_{0} \cdot \xi_0 + … + t_{N-1} \cdot \xi_{N-1}$. Since each signature is small-norm and each aggregation coefficient is small-norm, the aggregate signature $\xi_{ag}$ is small-norm. So we can check the norm, and we can check that $\langle \underline{a}, \xi_{ag} \rangle\xi_{ag} = t_ {0} \cdot (v_{0} \cdot c_{0} + u_{0}) + … + t_{N-1} \cdot (v_{N-1} \cdot c_{N-1} + u_{N-1})$ for $\texttt{AggregateVerify}$.

In [3], we introduced the lattice_algebra package and briefly described how it can be used to concisely implement this sort of scheme. The primary variation comes from tracking not only the infinity norm of secret signing key vectors, but also their Hamming weights.

We note that the security analysis in the paper [4] is rather pessimistic, and by tracking not only the infinity norm of secret vectors but also their Hamming weight, we may more tightly relate the norm of a linear combination of vectors or polynomials to the norms of its inputs and coefficients. We may also more tightly relate the two-norm with the infinity norm. This improved tightness in security inequalities expresses itself as smaller keys and signatures.

Verification Overhead for the BKLM Approach in a Lattice Setting

One practical consideration to note is that verifiers must compute the aggregation coefficients and transform them all with the ’number theoretic transform’ in order to verify a signature. The number theoretic transform takes time $O(d \cdot lg(d))$ to compute, so to compute one of these for each aggregation coefficient is $O(N \cdot d \cdot lg(d))$ computation time.

In particular, the methods of the BKLM scheme take at least $O(N \cdot d \cdot lg(d))$ additional verification time compared to linearly aggregated/stacked usual digital signatures, which has greater memory/space requirements than verifying individual digital signatures in series. Thus for a given application, the space and time tradeoffs must be carefully considered when assessing the utility of aggregation.

Conclusion

This article explored methods for sublinearly aggregating signatures, in the style of Boneh and Kim. We presented this idea from the perspective of extending a usual digital signature scheme to an aggregatable one. We noted that one can always trivially aggregate signatures by merely stacking them, which provides a baseline point of reference for assessing when signature aggregation is useful. We provided some back-of-the-napkin computations to ascertain the conditions and algebraic constraints under which signature aggregation is more efficient than stacking. The next article describes our novel one-time adaptor signature scheme, designed to enable payment channels and decentralized trustless cross-chain atomic swaps.

Writeup Contributors

Brandon Goodell, Mitchell “Isthmus” Krawiec-Thayer, Carlos Cid

Correspondence: info@geometrylabs.io

References

[1] Lyubashevsky, Vadim, and Daniele Micciancio. “Asymptotically efficient lattice-based digital signatures.” Theory of Cryptography Conference. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2008.

[2] Geometry Labs’ lattice-algebra repository on GitHub: https://github.com/geometry-labs/lattice-algebra

[3] TheQRL announcement of the lattice-algebra package: https://www.theqrl.org/blog/lattice-algebra-library/

[4] Boneh, Dan, and Sam Kim. “One-Time and Interactive Aggregate Signatures from Lattices.” (2020).

[5] Esgin, Muhammed F., Oğuzhan Ersoy, and Zekeriya Erkin. “Post-quantum adaptor signatures and payment channel networks.” European Symposium on Research in Computer Security. Springer, Cham, 2020.

[6] Tairi, Erkan, Pedro Moreno-Sanchez, and Matteo Maffei. “Post-quantum adaptor signature for privacy-preserving off-chain payments.” International Conference on Financial Cryptography and Data Security. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2021.

This article is part of the Techniques for efficient post quantum finance series.

- Introducing lattice-algebra: An elegant, high-performance post-quantum cryptography library

- Techniques for efficient post-quantum finance (Part 1: digital signatures)

- Selected: Techniques for efficient post-quantum finance (Part 2: signature aggregation)

- Techniques for efficient post-quantum finance (Part 3: adaptor signatures)

- Techniques for efficient post-quantum finance (Part 4: reducing storage requirements)

Proof of Stake technical research

28th April 2022