Techniques for efficient post-quantum finance (Part 1: digital signatures)

technical research proof-of-stake

14th April 2022

Table of Contents

This is the first article in a multipart series from The QRL Foundation and Geometry Labs exploring various methods for constructing scalable post-quantum cryptographic primitives and protocols.

Here in part one, we describe a lattice-based one-time signature scheme similar to the one published by Lyubashevsky and Micciancio. Since our scheme also has some similarities to CRYSTALS-Dilithium (a NIST post-quantum standardization candidate), there are general applications for our discussion below regarding optimizations for smaller keys and signatures in the lattice setting.

In the next article, we show how to extend this to Boneh and Kim style signature aggregation, as a potential method for reducing the on-chain footprint for proof-of-stake consensus with many validators. The following article describes our novel one-time adaptor signature scheme, designed to enable payment channels and decentralized trustless cross-chain atomic swaps (inspired by the work of Esgin, Ersoy, and Erkin).

The articles in this series describe the applications and security models; additionally, open-source python implementations of the cryptography are freely available via GitHub and PyPI (pip install lattice-cryptography), built with the lattice-algebra library described in a previous QRL blog post.

In the final part, we describe a blockchain-agnostic approach for reducing local storage requirements for network participants while keeping bootstrapping costs low.

Note: While some effort has gone into making everything understandable, the intended audience for this article series are systems integrators and students in cryptography. In order to help aid in understanding, we’ve added a further reading and materials section and will have an open AMA form for the duration of this “Techniques for post-quantum finance” series to ask any questions that may arise, both technical and non-technical. These writeups are intended to be informational, and the schemes described for illustration are not formal secure specifications.

Part One: Lattice-Based Digital Signatures

To set the stage for discussing one-time signatures, let us first introduce the general concept of a cryptographic signature.

Primer on Digital Signatures

A digital signature scheme refers to a tuple of algorithms (Setup, Keygen, Sign, Verify) which informally work as follows.

- $\texttt{Setup}(\lambda) \to \rho$. Input a security parameter $\lambda$, typically indicating the number of bits of security, and outputs some public parameters, $\rho$. Typically, $\rho$ contains a description of a secret signing key set, $K_S$, a public verification key set, $K_V$, a message set $M$, and a signature set $S$. $\texttt{Setup}$ is usually run by all parties before participating. The input and output of $\texttt{Setup}$ are both public.

- $\texttt{Keygen}(\lambda, \rho) \to (sk, vk)$. Input $(\lambda, \rho)$ and output a new random keypair $(sk, vk) \in K_S \times K_V$, where $sk$ is a secret signing key and $vk$ is the corresponding public verification key.

- $\texttt{Sign}(\lambda, \rho, (sk, vk), \mu) \to \xi$. Input $(\lambda, \rho, (sk, vk), \mu)$ where $\mu \in M$ is a message, and outputs a signature, $\xi \in S$.

- $\texttt{Verify}(\lambda, \rho, vk, \mu, \xi) \to b \in \left\{0, 1\right\}$. Output a bit $b$ indicating whether the signature is a valid signature on the message $\mu$ with the public verification key $vk$.

Since $\lambda$ and $\rho$ (the input and output of $\texttt{Setup}$, respectively) are shared parameters known by all participants, we will omit them as inputs below for readibility. Also, we assume that the message set $M$ is the set of all $k$-length bit strings, $M = \left\{0,1\right\}^k$ where $k$ is an (integral valued) function of $\lambda$.

Such a scheme is only secure if properly configured with appropriate parameters to achieve some desired security level. For illustration, consider a scheme where the output of $\texttt{Sign}$ is only 2 bits; it would take at most 4 tries to forge any signature! Or consider the situation if $\texttt{Verify}$ was a function that returns $1$ for most combinations of inputs; a high false positive rate for verification would be quite undesirable. These extreme examples show that both the functions and their parameters must be carefully selected. Formalizing this leads us to the notion of the security properties of digital signatures.

Security Properties: Correctness

Loosely, we say a signature scheme is “correct” whenever, for any message $\mu \in M$, and for any pair $(sk, vk)$ that is output from $\texttt{Keygen}$, it is the case that $\texttt{Verify}(vk, \mu, \texttt{Sign}((sk, vk), \mu)) = 1$. Correctness here is in analogy to soundness in zero-knowledge protocols. When considering security properties, it is often helpful to ask “what does it mean for a scheme to satisfy the negation of this property?”

For example, the negation of the correctness definition is as follows: there exists a message $\mu$ and a keypair $(sk, vk)$ that is output from $\texttt{Keygen}$ such that $\texttt{Verify}(vk, \mu, \texttt{Sign}((sk, vk), \mu)) = 0$. In this case, a scheme that does not satisfy the correctness property is not guaranteed to even produce signatures that pass verification!

Security Properties: Unforgeability

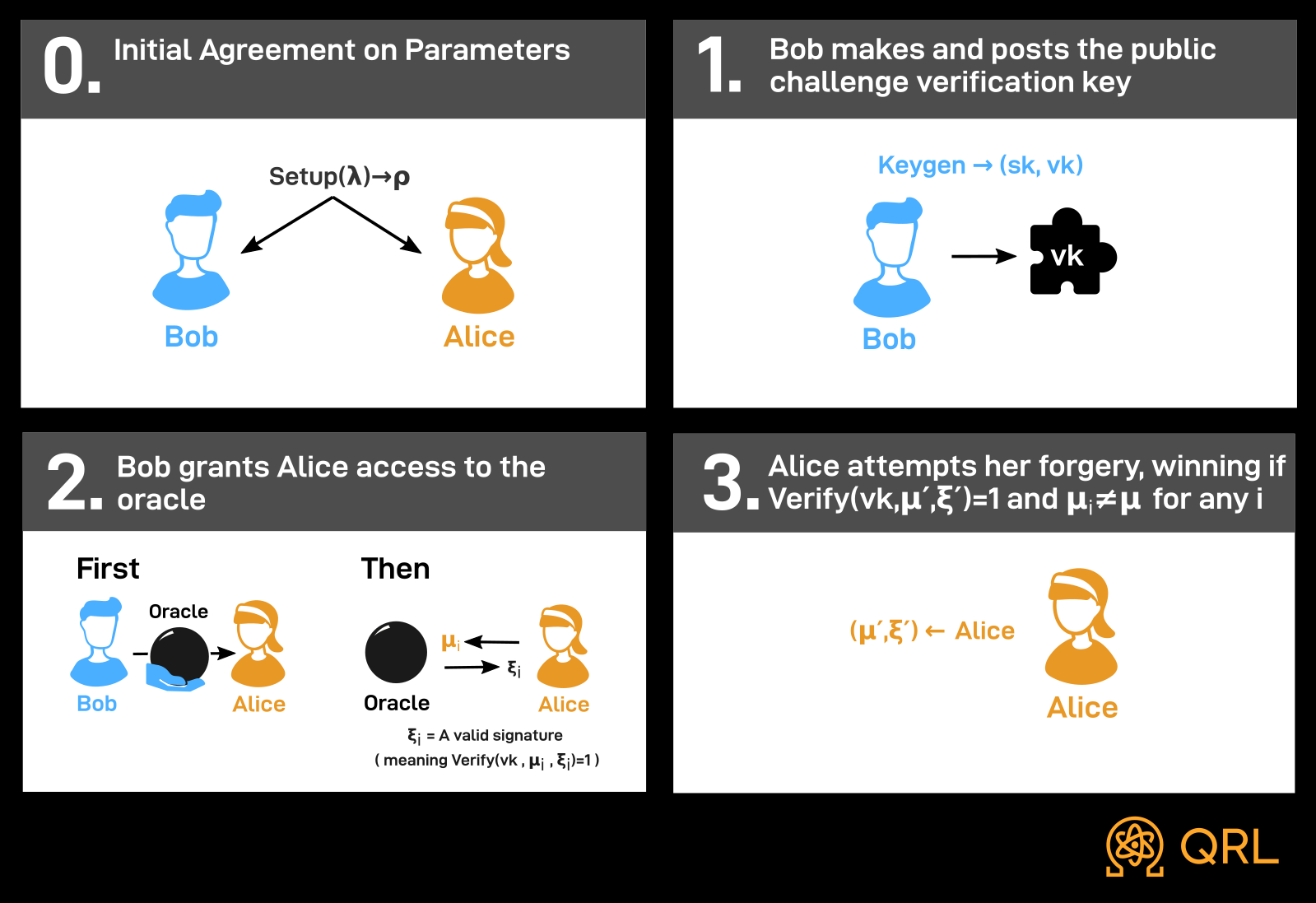

Now consider what it means for a signature scheme to be secure; more precisely, consider the notion of unforgeability. If Alice attempts to forge a usual digital signature without knowing Bob’s key, we can formalize this situation in a three-step process.

- First, Alice and Bob agree upon input and output of $\texttt{Setup}$. This models the real-life situation where $\lambda$ and $\rho$ are agreed-upon parameters that have been publicly audited and cryptanalyzed (e.g. by the NIST post-quantum signature vetting process).

- Next, Bob runs $\texttt{Keygen}$ to obtain some challenge keys $(sk, vk)$. Bob sends $vk$ to Alice.

- Lastly, Alice attempts to output some message-signature pair $(\mu, \xi)$. Alice’s forgery is successful if $\texttt{Verify}(vk, \mu, \xi) = 1$.

The idea behind unforgeability is that any algorithm “Alice” should fail at this game except with negligible probability.

There are two main things to note about this game. First, of course, the game is easy if Bob gives away his signing key ($sk$) to Alice, so it is critical that Alice learns no information about $sk$ in the course of the game in order for the result to be considered a successful forgery. Second, the game fails to capture the real-life situation where Alice may have seen signatures published under Bob’s key before, perhaps posted on some public bulletin board. Thus, Alice is often granted the benefit of the doubt and is given access to a signature oracle. This allows her to obtain a signature from Bob’s key on any message she likes, and also models the real-life situation where Alice may be able to coerce or trick Bob into signing a message that Alice has selected. However, in this case, Alice certainly should not be allowed to win the game by passing off an oracle-generated signature as a forgery. Moreover, Alice generally only cares about forging signatures for which she does not already have a signature. Hence, Alice is generally not interested in winning the game even by re-using any of the messages that have already been signed by the oracle.

This leads us to the following description of the existential unforgeability experiment. First, Alice and Bob agree upon the input and output of $\texttt{Setup}$. Next, Bob generates $(sk, vk)$ from $\texttt{Keygen}$ and sends $vk$ to Alice. Next, Bob grants Alice signature oracle access where she can query the oracle with any message $\mu$ and obtain asignature $\xi$ such that $\texttt{Verify}(vk, \mu, \xi) = 1$, in any order she likes, and she can adaptively select $\mu$ based on previous oracle responses. Eventually, Alice outputs a message-signature pair $(\mu^\prime, \xi^\prime)$, succeeding if and only if the signing oracle was not queried with $\mu$ and $\texttt{Verify}(vk, \mu^\prime, \xi^\prime) = 1$. This is visualized in the following diagram.

We then informally define a scheme to be existentially unforgeable if, for any algorithm “Alice”, the probability that Alice succeeds at this experiment is negligible. This is modeled by the Existential Unforgeability against Chosen Message Attack (EUF-CMA) security property, illustrated below.

As before, let us consider what it means to negate the definition of existential unforgeability. Then there exists an algorithm “Alice” that has a non-negligible probability of winning this game. This means that Alice, with no information about Bob’s $sk$ but perhaps with the ability to persuade Bob to publish some signatures on messages of Alice’s choice, can nevertheless produce a new forgery on a message Bob has never seen before.

Of course, we can expand this game to include more challenge keys; Bob could say “here are several of my verification keys, I challenge you to construct a valid signature on any one of them.” However, the number of keys provided to Alice is always polynomially bounded in $\lambda$, and thus Alice can at best polynomially improve her probability of success. In particular, if we can assume that Alice succeeds with only negligible probability in the one-key case, then Alice still can only succeed with negligible probability in the case that she is given a polynomial number of challenge keys, so it is not necessary to further consider this generalization.

Variations: One-Time Signature Schemes

A one-time signature scheme is just a digital signature scheme, even with the same definition of correctness, but with a different definition of unforgeability. In one-time schemes, producing more than one signature from the same key can reveal that key to other users, so it is only ever safe to publish one signature from any key; this makes one-time signatures particularly useful in constructing transaction protocols, as we shall see. However, this also means that our definition of existential unforgeability is no longer suitable. After all, in that definition, Alice can request many signatures from the signing oracle. To rectify this, the definition of the one-time existential unforgeability experiment is nearly identical to the existential unforgeability experiment, except Alice is only granted one oracle query.

Building Simple Signature Schemes

One-time signature schemes are oftentimes very simple to describe and implement, which leads to straightforward proofs of security properties and mistake-resistant code. In the following examples, we show a case from classically secure cryptography and a similar case from quantum-resistant cryptography. As we can see from the descriptions below, the schemes are quite simple, so implementing them requires navigating fewer pitfalls than implementing more complex signature schemes.

Example: A Schnorr-Like One-Time Signature Scheme

In this section, we describe a Schnorr-like signature scheme in the elliptic curve setting. Let $\mathbb{G}$ be an elliptic curve group, written additively, with prime order $p$, and let $G$ be generator, and let $F:\left\{0,1\right\}^* \to \mathbb{Z}/p\mathbb{Z}$ be a hash function modeled as a random oracle. The following defines a one-time signature scheme that satisfies one-time existential unforgeability.

- $\texttt{Setup}(\lambda) \rightarrow \rho$. Set $\rho = (\mathbb{G}, p, G, F)$.

- $\texttt{Keygen} \rightarrow (sk, vk)$. Sample $x, y \in \mathbb{Z}/p\mathbb{Z}$ independently and uniformly at random, set $X := xG$, $Y := yG$, $sk := (x, y)$, and $vk := (X, Y)$. Output $(sk, vk)$.

- $\texttt{Sign}((sk, vk), \mu) \rightarrow \xi$. Compute $c = F(vk, \mu)$, parse $(x, y) \leftarrow sk$, set $\xi := x \cdot c + y (\text{mod}, p)$, and output $\xi$.

- $\texttt{Verify}(vk, \mu, \xi) \rightarrow b$. Check that $\xi$ can be interpreted as an element of $\mathbb{Z}/p\mathbb{Z}$, compute $c = F(vk, \mu)$, and output $1$ if and only if $\xi G = c X + Y$.

The scheme is correct. Indeed, if $x, y, c \in \mathbb{Z}/p\mathbb{Z}$ (which is a field, and thus closed under addition and multiplication), then so is $x \cdot c + y$. Consider a semi-honest actor, who follows the alogrithms above, but may execute additional computations as well. So a signature $\xi$ computed this way is an integer modulo $p$ since $x$, $c$, and $y$ are integers modulo $p$. Also, since $\texttt{Sign}((sk, vk), m) = x \cdot c + y$, we have that $(x \cdot c + y)G = c \cdot X + Y$. The scheme can also be shown to be unforgeable, by giving Alice only one oracle signature $\xi_0$ and showing that if Alice can produce a forgery, then Alice can also break the discrete logarithm assumption. Indeed, if Alice can produce $\xi$ that satisfies the game, and receives an oracle-generated signature $\xi_0$, then Alice can compute $\xi - \xi_0$ easily and solve backward for $x$ and $y$. We note that in a one-time signature scheme, producing a forgery is equivalent to breaking a public verification key, because producing the forgery is enough together with the one-time oracle signature, to back-compute the keys. This is, in fact, a common property of one-time signature schemes: publish two signatures and you give away your private key. Bellare and Shoup prove that this one-time signature scheme is unforgeable up to the the one-more discrete-log assumption (see [4]). At the end, she will have successfully gained enough information to easily compute the discrete logarithm of $X$. Since computing discrete logarithms is hard with classical computers, we conclude that classical forgers do not exist (or succeed with very low probability, or take a very long time to finish their tasks).

Example: Extending this Schnorr-Like Approach to the Lattice Setting

We can swap out the fundamental hardness assumption above with a different hardness assumption to get a different scheme; using a related approach, Lyubashevsky and Micciancio first proposed signatures designed (mostly) this way in [1]. In a lattice setting, we ditch the elliptic curve group in favor of lattices induced by rings of integers and their ideals. Let $\mathbb{Z}/q\mathbb{Z}$ be the integers modulo $q$ for a prime modulus $q$, let $d$ be a power-of-two integer, let $\ell$ be a natural number, let $R = \mathbb{Z}\left[X\right]/(X^d + 1)$ be a quotient ring of integer-coefficient polynomials, let $R_q$ be the quotient ring $R/qR$, let $V = R^\ell$ be the freely-generated $R$-module with length/dimension/rank $\ell$, and let $V_q = R_q^\ell$ be the freely-generated $R_q$-module with length $\ell$. Note that $V$ is a $\mathbb{Z}$-module and $V_\mathfrak{q}$ is a $\mathbb{Z}_q$-module, both with dimension $d\cdot\ell$. Elements $f(X) \in R$ have an infinity norm; if $f(X) = f_0 + f_1 X + … + f_{d-1} X^{d-1}$, then $\|f\|_\infty = \max(|f_i|)$. This definition extends to $V$, which is convenient.

We can similarly extend this definition to $R_q$ and $V_q$, but at a cost. The cost we pay is in absolute homogeneity. In a vector space $U$ over a field $F$, for any scalar $c \in F$ and any vector $u \in U$, absolute homogeneity is the property that $\|c \cdot u\| = |c| \|u\|$, where $|c|$ is computed by lifting $c$ from $F$ to $\mathbb{C}$, the complex numbers. If we carry our definition of $\|\cdot\|_{\infty}$ from $R$ to $R_q$, or from $V$ to $V_q$, we cannot use this statement to conclude anything about the norm of $c \cdot u$ when $c\in$ $R$ or $R_q$ (except in the special cases that $c \in \mathbb{Z}/q\mathbb{Z}$).

In fact, absolute homogeneity is relaxed in $R$ and $R_q$, and we end up with a norm-like function with absolute subhomogeneity: $\| c \cdot u\| \leq d \cdot |c| \|u\|$.

For lack of a better term, we shall call such functions subhomogeneous norms, and if $T$ is a space that admits a sub-homogeneous norm, we shall call $T$ a subhomogeneously normed space.

In the following, we describe a scheme sketched by Boneh and Kim in [4] which is inspired by the scheme from Lyubashevsky and Micciancio in [1]. Let $\beta_{sk}$, $\beta_{ch}$, $\beta_v \in \mathbb{N}$. For any subset $T$ of any subhomogeneously normed space, let $B(T, \beta) = \{t \in T \mid \|t\|_{\infty} \leq \beta\}$. Again let $F$ be a hash function modeled as a random oracle, but this time, let $F:\left\{0,1\right\}^* \to B( R_q, \beta_{ch})$.

- $\texttt{Setup}(\lambda) \rightarrow \rho$. Compute $d, q, l, k, \beta_{sk}, \beta_{ch}, \beta_v$ from $\lambda$, sample $\underline{a}$ from $V_q$ uniformly at random, and output $\rho = (d, q, l, F, k, \beta_{sk}, \beta_{ch}, \beta_v, \underline{a})$. The signing key set is $K_S = B(V_q, \beta_{sk}) \times B(V_q, \beta_{sk})$, the verification key set is $K_V = R_q \times R_q$, the message set is length $k$ bit strings $M = \left\{0, 1\right\}^k$, and the signature set is $S = B(V_q, \beta_v)$.

- $\texttt{Keygen} \rightarrow (sk, vk)$. Sample $\underline{x}, \underline{y}$ uniformly at random and independently from $B(V_q, \beta_{sk})$. Set $sk = (\underline{x}, \underline{y})$. Define $X = \langle \underline{a}, \underline{x}\rangle$ and $Y = \langle \underline{a}, \underline{y}\rangle$ and set $vk = (X, Y)$. Output $(sk, vk)$.

- $\texttt{Sign}((sk, vk), \mu) \rightarrow \xi$. Compute $c = F(vk, \mu)$ and output $\xi = \underline{x} \cdot c + \underline{y}$ where $\cdot$ here denotes scaling the polynomial vector $\underline{x} \in B(Vq, \beta_{sk})$ with the polynomial $c \in B(R_q, \beta_{ch})$.

- $\texttt{Verify}(vk, \mu, \xi) \rightarrow b$. Check that $\xi$ is an element of $B(Vq, \beta_v)$, compute $c = F(vk, \mu)$, and output $1$ if and only if $\langle \underline{a}, \xi\rangle = X \cdot c + Y$.

We note that an honestly computed signature $\xi = \underline{x} c + \underline{y}$, and $|\xi| \leq \beta_{sk}(1 + d\beta_{ch})$. Hence, if $\beta_{sk}(1+d\beta_{ch}) \leq \beta_{vf}$, then the scheme is correct. Similarly to the previous scheme, this scheme can be proven unforgeable (see [1] and [4]).

Optimizing One-Time Lattice-Based Signatures

The security properties for lattice-based schemes often are based on requiring that public keys are covered by a sufficiently dense set of private keys. This ensures that the short solution $\underline{t}$ to the Ring Short Integer Solution problem is non-zero at least half the time. However, direct implementations of these schemes often lead to unnecessarily dense key coverage.

For example, consider the requirement that a uniformly sampled element from the domain of the maps which carry the secret keys $(\underline{x}, \underline{y})$ to the public keys and a signature $(X, Y, \xi)$ always has a distinct second pre-image $(\underline{x}^\prime, \underline{y}^\prime)$. What sort of requirements does this place on the system parameters? Well, for any function $f: A \to B$, at most $|B|$ elements map uniquely under $f$.

Hence, if an element $a$ is sampled from $A$ uniformly at random, then there is a probability at most $|B|/|A|$ that $f( a)$ has no other pre-images $a^\prime$. To ensure this probability is less than $2^{-\lambda}$, we require that $|B| \cdot 2 ^ \lambda < |A|$.

The domain of our map is pairs of elements from $B(V_q, \beta_{sk})$. Thus, the size of the domain is the square of the size of $B(V_q, \beta_{sk})$. Moreover, an element of $B(V_q, \beta_{sk})$ is an $\ell$-vector of polynomials whose coefficients are absolutely bounded by $\beta_{sk}$, which means all coefficients are in the list $\{-\beta_{sk}, -\beta_{sk} + 1, …, \beta_{sk} - 1, \beta_{sk}\}$, which clearly has $2 \beta_{sk} + 1$ elements in it. All such vectors are allowable, each has exactly $\ell$ coordinates, and each of those has exactly $d$ coefficients. There are necessarily $(2\beta_{sk} + 1)^{\ell d}$ such vectors, so there are $(2\beta_{sk}+ 1)^{2\ell d}$ elements in the domain of our map.

On the other hand, the codomain of our map is tuples containing pairs of public keys and signatures. Each public key is a polynomial in $R_q$, and may be unbounded. So we have $q^{2d}$ possible public verification keys. On the other hand, the signature is a polynomial vector with coefficients absolutely bounded by $\beta_{v}$. Hence, we have $(2 \beta_ {v}+1)^{\ell d}$ possible signatures. In particular, we have $q^{2d} \cdot (2\cdot\beta_{v} + 1)^{\ell d}$ elements in the codomain. So one requirement for security is that $\frac{(2\beta_{sk}+1)^{2\ell d}}{q^{2d} (2\beta_{v} + 1)^{\ell d}} > 2^\lambda$.

Now, on the other hand, we may be able to use sparse keys in order to make this inequality easier to satisfy. This technique is referred to in the CRYSTALS-Dilithium documentation as “hashing to a ball.” In particular, we can consider a variation of the Schnorr-Like approach to the lattice setting wherein private keys are not just polynomial vectors whose infinity norms are bounded by $\beta_{sk}$, but whose Hamming weights are also bounded by some $1 \leq \omega_{sk} \leq d$. We can similarly put a bound on the Hamming weight (the number of nonzero coefficients) of the signature challenge $c$ by some $1 \leq \omega_{ch} \leq d$, and we will consequently be bounding the Hamming weight of signatures by some $1 \leq \omega_ {v} \leq d$. In this case, our inequality constraint changes to become a significantly more complicated inequality involving binomial coefficient computations, which we omit for the sake of readability. If we carefully select $\omega_ {sk}$, $\omega_{ch}$, and $\omega_{v}$, the above bound can be tightened or loosened. Using this technique, we can describe signatures and keys with less space than otherwise. For example, if $\omega_{v} = d/8$ and $d = 512$, then we can save at least $134$ bits per signature with efficient encoding of the signature. However, this choice may make the inequality in question harder to satisfy (recall that the inequality in question guarantees second pre-images occur often enough).

Transaction Protocols And Usual Digital Signatures

For the purposes of this discussion, a transaction is a tuple (I, O, FEE, MEMO, AUTH) where I is a set of input keys, O is a set of output keys, FEE is a positive plaintext fee, AUTH is an authentication of some sort, and MEMO is an optional memo field. The transaction can be seen as consuming the input keys and creating new output keys; in fact, every input key in a transaction must be an output key from an old transaction, and whether a key is an input or an output key is therefore highly contextual. The outputs are injected into the system via work or stake rewards, which allow users to authorize special negative-fee transactions. Users broadcast these transactions on any network however they agree upon, validators assemble valid transactions into valid blocks with whatever block puzzles they agree upon, and they order these blocks into a sensible linear transaction history using whatever consensus mechanism they agree upon.

A transaction protocol can be built using a public bulletin board (upon which transactions are posted), together with some sort of map or lookup called AMOUNT that maps outputs to plaintext transaction amounts. A transaction posted on the bulletin board is considered valid if every input reference points to a valid transaction, the signatures in the authentication AUTH are valid, and AMOUNT(I) - AMOUNT(O) - FEE = 0. Obviously this leads to a regression of valid transactions, which must terminate at some sort of root transaction.

These root transactions are known as base transactions or coinbase transactions. Base transactions are special transactions that (i) include a block puzzle solution in AUTH and (ii) have a deterministically computed FEE < 0, called the block reward. In a proof-of-work cryptocurrency, the block puzzle solution is often the input to a hash function that produces a sufficiently unlikely output. In a proof-of-stake cryptocurrency, this block puzzle solution is a signature by validators that have been decided upon in advance somehow.

From this point of view, then, to describe a transaction protocol is to (i) describe the structure of (I, O, FEE, MEMO, AUTH), (ii) describe AMOUNT, (iii) decide upon a block puzzle solution method for the protocol, and (iv) decide upon a deterministically computed block reward.

Generally I can be lazily described using any unambiguous reference to a set of outputs from the transaction history, such as a list of block height-transaction index-output index triples, and FEE is a plaintext amount in every transaction. We can allow any bitstring memorandum message, but we prepend any user-selected memorandum with a bitstring representation of the tuple (I, O, FEE). In practice, AUTH generally consists of a multi-signature with the keys described in $I$ on the pre-pended memorandum message.

We need to stash into each output both a verification key from some unforgeable signature scheme and also some way of measuring amounts. We can accomplish this with no privacy whatsoever by making an output key of the form $(vk, \alpha)$ where $\alpha$ is a plaintext amount and $vk$ is a public verification key from the underlying signature scheme. In this case, the AMOUNT function merely forgets the verification key $vk$ and outputs $\alpha$.

To summarize, using an unforgeable signature scheme as a sub-scheme, we use the following structure of general transactions for a transparent cryptocurrency.

- The list of inputs

Iin a transaction consist of triples of the form(block_hash, transaction_id, output_index). Any validator with a block referenced by this transaction can easily look up an old output key from an old transaction in their ledger this way. This is assumed to be ordered in a canonical way. - The list of new outputs

Oconsists of verification key-amount pairs $(vk, \alpha)$ where $vk$ is a verification key from the sub-scheme and $\alpha$ is a positive plaintext amount. This is assumed to be ordered in a canonical way. Thus, each(block_hash, transaction_id, output_index)refers to an output key $(vk, amt)$ in the validator’s local copy of the blockchain. - The fee

FEEis a user-selected positive amount. - The memo

MEMOis a user-selected bitstring. - The authentication

AUTHconsists of a multi-signature on the messageMSG = I || O || FEE || MEMOwhere||denotes concatenation, signed by the inputs, i.e. the keys found at the input references.

Recalling that concatenating usual digital signatures together is a trivial way of making a multi-signature scheme, we see that we can simply stack signatures to accomplish this protocol. This way, anyone with the secret signing keys $sk_ {old}$ associated to an output verification key $vk_{old}$ in some old valid transaction can construct a new valid transaction sent to any target verification key $vk_{new}$ by simply signing the zero bit and setting the amounts.

However, this approach re-uses the verification keys of a user, so this approach does not carry over directly to one-time signature schemes. This is easily rectified, as we see in the next section.

Transaction Protocols And One-Time Signatures

We can use one-time signatures in a transaction protocol to introduce a degree of unlinkability, if we like, but we need some sort of key exchange. This way, we can ensure that the recipient can extract the new one-time signing keys associated with their new outputs, whilst ensuring that the sender cannot extract that key. We can introduce auditor-friendly unlinkability by introducing one-time keys and using CryptoNote-style view keys.

Example: Monero/CryptoNote-Style One-Time Keys

CryptoNote used the computational Diffie-Hellman assumption and hash functions in order to construct one-time keys from many-time wallet keys. We show how this key exchange can be used to develop an amount-transparent and non-sender-ambiguous version of CryptoNote that is nevertheless unlinkable and auditor-friendly.

In the following, let $(\mathbb{G}, p, G, F)$ be the group parameters from our Schnorr-like example of one-time signatures.

- In a setup phase, users agree upon $(\mathbb{G}, p, G, F)$, and another hash function $H:\left\{0,1\right\}^* \to \mathbb{Z}/p\mathbb{Z}$.

- Users select many-time wallet keys by sampling $a, b \in \mathbb{Z}/p\mathbb{Z}$ independently and uniformly at random. Users set $A = aG$, $B = bG$, $sk = (a, b)$, and $vk = (A, B)$. Users then broadcast $vk$.

- An output is a tuple $(R, P, \alpha)$ where $R$ and $P$ are group elements and $\alpha$ is a plaintext amount.

- To send an amount $\alpha$ to another user with some $vk = (A, B)$, a new output $(R, P, \alpha)$ is constructed in the following way. First, we sample a new random $r \in \mathbb{Z}/p\mathbb{Z}$ independent of all previous samples and uniformly at random, and we set $R = rG$. Next, we use $r$ and the recipient $A$ to compute the Diffie-Hellman shared secret $rA = aR$. We hash this with $H$ and compute $P = H(rA)G + B$.

- A user can easily determine if a new output $(R, P, \alpha)$ is addressed to their own $vk$ by checking if $P = H(aR) G + B$.

- To send an old output $(R, P, \alpha)$, the amounts must balance and the sender must include a signature on the key $P$ in their authentication.

Under the Computational Diffie-Hellman assumption, only the recipient (owner of $a$) and the sender (who knows $r$) can compute $rA = aR$, so only the sender and the recipient can link the output $(R, P, \alpha)$ with the wallet keys $(A, B)$. This leads to one-time keys in the sense that only one signature ever needs to be posted in order for a transaction to be considered valid and complete. However, depending on the properties of the underlying signature scheme, it may or may not be safe to publish more than one signature from a key $P$. Moreover, the privacy gained from such an approach is rather minimal, as the one-time addresses can easily be probabilistically linked with one another by a studious third party. Note that to determine whether a transaction is addressed to $(A, B)$, the recipient only need the private key $a$, which is why we call it a view key. On the other hand, we call $b$ a spend key because we need it to construct new transactions.

The overall approach itself is a rather inelegant instantiation of a key encapsulation mechanism, and the one-time-ness of the protocol can be a “soft” one-time-ness. By using a proper key encapsulation mechanism and one-time signatures, we can make this a bit of a tighter ship.

A Brief Aside: Key Encapsulation Mechanisms

A key encapsulation mechanism (KEM) is a tuple of algorithms $(\texttt{Setup}, \texttt{Keygen}, \texttt{Enc},\texttt{Dec})$ which work as follows.

- $\texttt{Setup}(\lambda) \to \rho$ inputs a security parameter $\lambda$ and outputs some public parameters $\rho$.

- $\texttt{Keygen} \to (sk, pk)$. Output a new secret-public keypair $(sk, pk)$.

- $\texttt{Enc}(pk) \to (c, ek)$. Input a public key $pk$ and output a ciphertext $c$ and a bitstring $ek$ we call an ephemeral key.

- $\texttt{Dec}(sk, c) \to \left\{ek, \bot\right\}$. Inputs a secret key $sk$ and a ciphertext $c$, and outputs a bitstring $ek$ or a distinguished failure symbol $\bot$.

Setting aside the security properties of a key encapsulation mechanism (that’s a different article!), the rough ideahere is to compute $(c, ek) \leftarrow \texttt{Enc}(pk)$ and use $ek$ as a symmetric key to encrypt a message $\mu$,resulting in another ciphertext $d$. You then send $(c, d)$ to the owner of $pk$, who can use their $sk$ to compute $ek\leftarrow \texttt{Dec}(sk, c)$, and then use $ek$ to decrypt $d$ to obtain $\mu$.

Example: Extending to Lattice-Based One-Time Keys

In the following, let $(d, q, l, k, F, \beta_{sk}, \beta_{ch}, \beta_{v}, \underline{a})$ be output from $Setup$ in the Schnorr-like approach to the lattice setting, let $\beta_t$ be some natural number, let $H_0, H_1:\left\{0, 1\right\}^* \to B(V_q, \beta_t)$ and let $(KEM.Setup, KEM.Keygen, KEM.Enc, KEM.Dec)$ be a secure KEM.

- In a setup phase, users agree upon all the above parameters, hash functions, and so on.

- Users select many-time wallet keys $(sk, vk)$ in the following way. To sample $sk$, the user computes $(KEM.sk,KEM.pk) <- KEM.Keygen$, samples a new random $x_0, x_1$ uniformly at random from $B(V_q, \beta_{sk})$, computes $X_0= \langle \underline{a}_0, \underline{x}_0\rangle$, $X_1 = \langle \underline{a}_0, \underline{x}_1\rangle$ and sets$sk = (KEM.sk, x_0, x_1)$. They then use $vk = (KEM.vk, X_0, X_1)$.

- An output is a tuple $(c, h_0, h_1, \alpha, \pi)$ where $c$ is a ciphertext from the KEM, $h$ and $g$ arepolynomials, $\alpha \in \mathbb{N}$ is a plaintext amount, and $\pi$ is a zero-knowledge proof of knowledge (ZKPOK).We will elaborate on this proof of knowledge in a moment.

- An authorization to send an output is just a one-time signature using $vk = (h_0, h_1)$.

- To send an amount $\alpha$ to another user with some $vk = (KEM.pk, X_0, X_1)$, a new output $(c, h_0, h_1, \alpha, \pi)$ is constructed in the following way. First, we encapsulate a new ephemeral key for $KEM.pk$ by computing $(c, ek) <- KEM.Enc(KEM.pk)$. Next, we compute $\underline{b}_0 = H_0(ek)$ and $\underline{b}_1 = H_1(ek)$ and set $h_i = X_i + \langle \underline{a}, \underline{b}_i\rangle$ for $i=0, 1$. Next, we compute a ZKPOK $\pi$. The sender can publish $(c, h_0, h_1, \alpha, \pi)$.

- Upon hearing of a new transaction, a user can easily determine if a new output $(c, h_0, h_1, \alpha, \pi)$ is addressed to their own $vk$ by checking if $KEM.Dec(KEM.sk, c) != FAIL$, can manually check the plaintext amounts to verify that no money was created or destroyed. To obtain the signing keys corresponding to the public verification key $vk = (h_0, h_1)$, the user takes their $KEM.sk$, decapsulates $c$ to obtain $ek$, computes $\underline{b}_i = H_i(c, ek)$, and then computes $\underline{z}_i = \underline{x}_i + \underline{b}_i$. The user then verifies that $h_i = \langle \underline{a}, \underline{z}_i \rangle$ for both $i=0, 1$.

Of course, the recipient can be assured that the extracted keys $(\underline{z}_0, \underline{z}_1)$ will work by checking the ZKPOK $\pi$. In particular, the ZKPOK $\pi$ in the output $(c, h_0, h_1, \alpha, \pi)$ must be a valid proof of knowledge of some secret $(KEM.pk, X_0, X_1)$ and a secret ephemeral key $ek$ such that $(c, ek) \leftarrow KEM.Enc(KEM.pk)$ and each $h_i = X_i + \langle \underline{a}, H_i(c, ek)\rangle$.

Note that for this scheme to be secure, it is sufficient that all the following conditions hold.

- All our hash functions are cryptographically strong against finding second pre-images.

- The KEM is secure.

- The signature scheme is unforgeable.

- The proving system used to generate and validate the ZKPOK $\pi$ must be sound and complete.

Summary

In this article we described how to efficiently implement lattice-based signatures. We discussed some simple signature designs, and their security properties, in the elliptic curve setting to motivate discussion on these in the lattice-based settings. We showed how lattice-based signatures can be made more efficient with sparse keys, and we link to a python package we developed that employs these signatures. We described how transaction protocols can be built from both usual and one-time digital signature schemes. Lastly, we showed a very simple implementation of a transaction protocol that uses Key Encapsulation Mechanisms and one-time lattice-based signatures. The next article will show how to extend this scheme for signature aggregation.

Writeup Contributors

Brandon Goodell, Mitchell “Isthmus” Krawiec-Thayer, Carlos Cid

Correspondence: info@geometrylabs.io

References

[1] Lyubashevsky, Vadim, and Daniele Micciancio. “Asymptotically efficient lattice-based digital signatures.” Theory of Cryptography Conference. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2008.

[2] Geometry Labs’ lattice-algebra repository on GitHub: https://github.com/geometry-labs/lattice-algebra

[3] TheQRL announcement of the lattice-algebra package: https://www.theqrl.org/blog/lattice-algebra-library/

[4] Boneh, Dan, and Sam Kim. “One-Time and Interactive Aggregate Signatures from Lattices.” (2020).

[5] Esgin, Muhammed F., Oğuzhan Ersoy, and Zekeriya Erkin. “Post-quantum adaptor signatures and payment channel networks.” European Symposium on Research in Computer Security. Springer, Cham, 2020.

[6] Tairi, Erkan, Pedro Moreno-Sanchez, and Matteo Maffei. “Post-quantum adaptor signature for privacy-preserving off-chain payments.” International Conference on Financial Cryptography and Data Security. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2021.

Further Reading and Materials

General cryptography courses/books

The intended audience for this article series is student cryptographers and systems integrators. While anyone is encouraged to to read through, understanding everything without some amount of background in the cryptography might be difficult.

If you’re interested in the subject, we would recommend:

- Dan Boneh’s Cryptography course on Coursera,

- Steven Galbraith’s book “Mathematics of Public Key Cryptography”

- Introduction to Modern Cryptography

LMsigs (Lyabashevsky and Micciancio) background reading for this article

An analysis of a scheme similar to the discrete logarithm-based Schnorr-like signature scheme we use as our first example: https://eprint.iacr.org/2012/029.pdf

The background for lattice signatures comes from the following:

- The lattice signature analogue to this Schnorr-like scheme can be found here: https://crypto.stanford.edu/~skim13/agg_ots.pdf

- Outdated review of knowledge: https://web.eecs.umich.edu/~cpeikert/pubs/lattice-survey.pdf

- Another: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/11818175_8.pdf

- This style of lattice signatures was first proposed by Lyubashevsky and Micciancio here: https://eprint.iacr.org/2013/746.pdf

- The crystals dilithium paper: https://pq-crystals.org/dilithium/

- We discuss a general model of transaction structures that was (afaik) first introduced here: https://blockstream.com/bitcoin17-final41.pdf

- CryptoNote-style one-time keys: https://www.getmonero.org/ru/resources/research-lab/pubs/whitepaper_annotated.pdf

- Key Encapsulation Mechanisms: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-540-76900-2_29

- Unforgeability and correctness are the bare minimum security properties we should expect, but there are other, stronger notions of security we should prefer, see: https://eprint.iacr.org/2020/1525.pdf

This article is part of the Techniques for efficient post quantum finance series.

- Introducing lattice-algebra: An elegant, high-performance post-quantum cryptography library

- Selected: Techniques for efficient post-quantum finance (Part 1: digital signatures)

- Techniques for efficient post-quantum finance (Part 2: signature aggregation)

- Techniques for efficient post-quantum finance (Part 3: adaptor signatures)

- Techniques for efficient post-quantum finance (Part 4: reducing storage requirements)

Proof of Stake technical research

14th April 2022